Living half your life as a sighted person and half as a blind man, the contrast makes for strange bedfellows — memories and present experiences crashing powerfully together in an unparalleled way.

Living half your life as a sighted person and half as a blind man, the contrast makes for strange bedfellows — memories and present experiences crashing powerfully together in an unparalleled way.

Before going totally blind I was a drama coach for several summers at Camp Coleman in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in northern Georgia. The last weekend of this past August was a celebration marking the 50th birthday of this profound place. All folks who worked on the staff as well as any campers who attended over the years were invited up for the weekend fete.

When you see a fine film that resonates with you, you may tend to replay it in your head, maybe even watching it again from time to time. Vivid images take up residence in your brain and over time, something triggers them, like an old song that catches your ear in a mall, filling the screen in your mind with pictures of an old friend, lover or special place with remarkable precision. The actors in a favorite film continue to inhabit your brain, never aging, never changing, and forever vibrant. Being sighted those many summers ago and now being blind, those campers and staffers that filled my summertime landscape remain in my headlike rare movies.

When the tires of the rental car started popping the pebbles of the gravel road on the long path leading up to the campground a few days ago, the images and memories were triggered straightaway, emotionally charged sounds and smells soon to follow; chirping crickets, the clean scent of mountain air warming my nose, the sun pure and free of humidity, all hit simultaneously and was intoxicating. It’s probably true that “you can’t go home again,” but you can certainly visit with enormous passion.

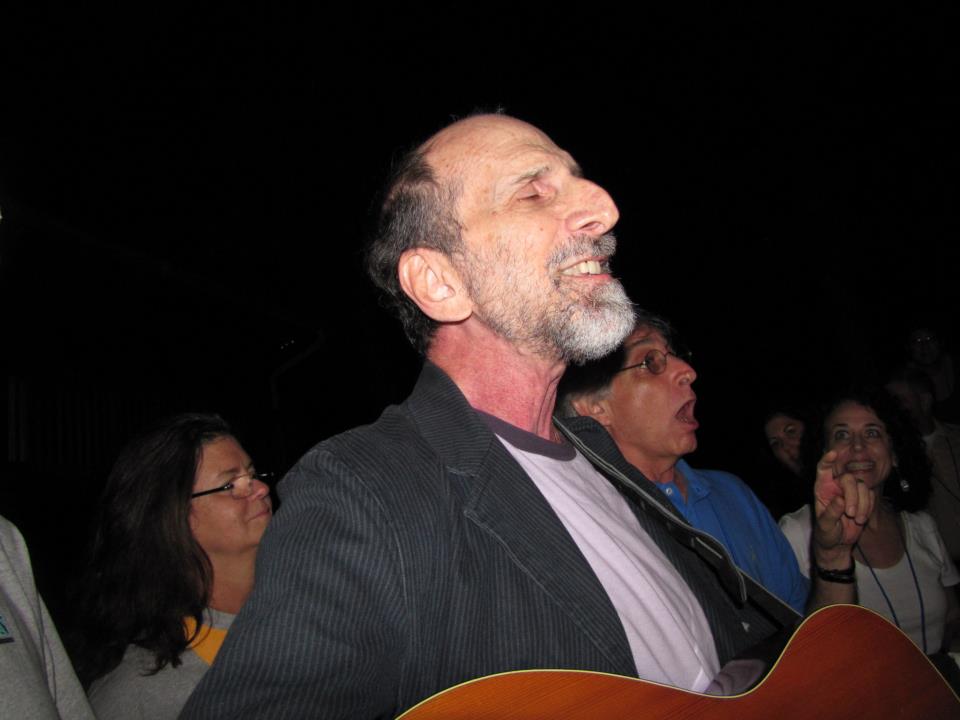

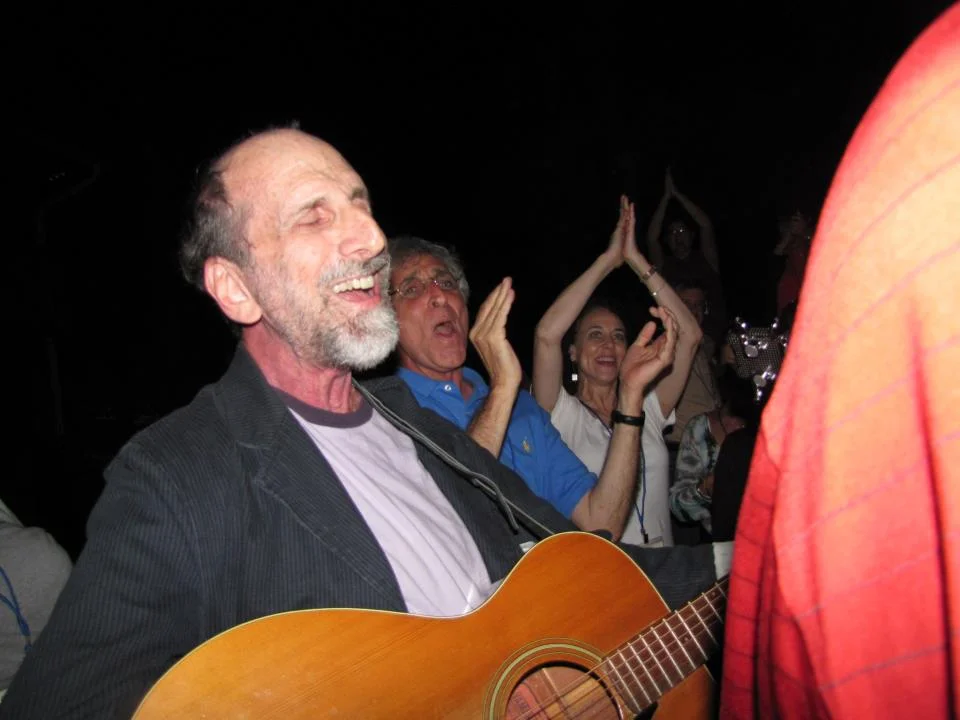

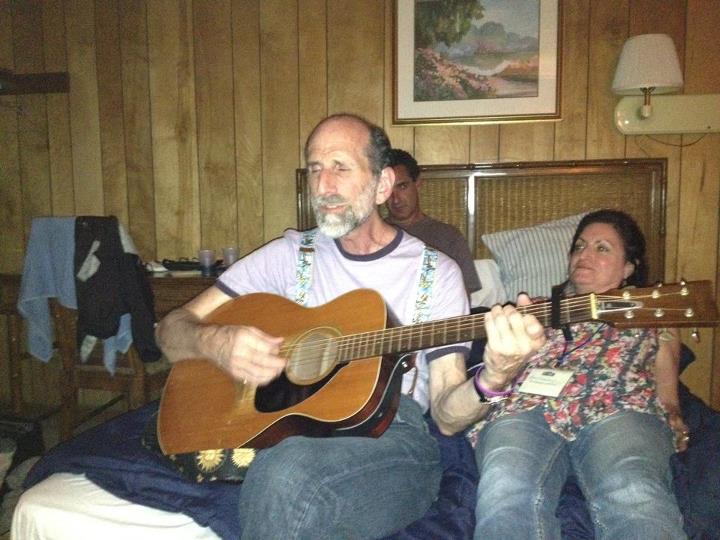

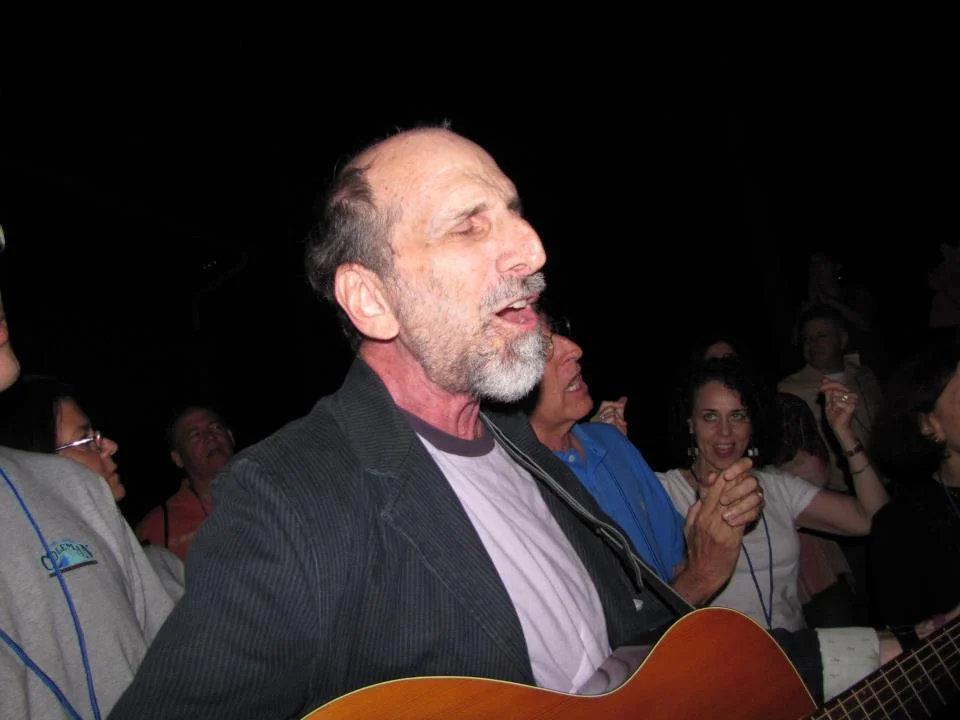

To attempt to capture the enormity of these moments in the mountains with words would be folly. I can tell you that music was the connective tissue both then and now; to be with neural psychologists, doctors, lawyers, performers, TV producers, captains of industry, financial brokers, artists, all stomping their feet, grinning, holding hands and singing camp tunes with abandon converged to this single point: what we all had accomplished with our lives was no more monumental than what we accomplished as campers, the environs and the people shaping our hearts and filling our souls with all the emotional tools to embrace what was just up ahead. This was indeed the stuff of Martin Luther King Jr. and his dream for “content of character.”

The stones crunching under my sneakers as I walked these unmatched grounds as a blind man, I visited the open air theater where I directed the big shows. Thumping my feet and hearing the hollowness of the boards brought images of the colored gels, the wooden platforms, the piano that served as an entire orchestra, and of course the kids. I was charged with producing the camp musical presented on the final night before we all dispersed back to our individual homes. I had to choose shows that I could populate with a gaggle of campers – a swarm of townspeople in “The Music Man,” super sized gangs of Jets and Sharks in “West Side Story,” 11 thousand gold miners in “Paint Your Wagon.” So many on this weekend reunion were players in these shows (one talented young lady has now been living in L. A. for almost 40 years as a successful actor!), and as I spoke to several of them, there was a little kid’s curious and hopeful face superimposed on top of the voices of these very grown up people –an uncanny and profound image I could not have if I was sighted.

I felt the wooden rail along the brief bridge to the admin building and while I was dodging the splinters, I recalled a conversation with my wonderful camp director, Alan. I was conflicted about whether to return to camp the next year as drama coach or pursue summer stock. After a moment of reflection, I said to Alan, “Maybe I should do summer stock so I can get this acting thing out of my system.” His reply: “Or get it into your system.” That was my last summer at camp; I’ve been acting ever since.

I walked up the great steps to the old dining hall (now an art center) and once inside, I went to the center of the hall and placed my hand on the stone chimney where I played Puff the magic dragon. No, I didn’t sing the Peter, Paul and Mary tune – that was the job of the song leader. I played Puff himself. Whenever it was sung after a meal, I would spontaneously combust, twisting my face and tongue, stretching my arms to the ceiling, and would hop from table top to table top as 300 kids screamed with delight at my silly antics. During the final verse on the line, “So Puff that mighty dragon sadly slipped into his cave!” I climbed up into the chimney and perched myself onto a ledge that was about a foot above the chimney’s opening. During the final chorus, I lowered myself to where only my up-side-down head could be seen to the camper's sheer joy.

What amazed me was when camper after camper came up to me this weekend and expressed their fond memory of Puff and “how it changed them.” Changed them? How could a silly little creature have this effect? It struck me that the dragon inspired so many little kids to be what they wanted to be, perhaps many of them not receiving this encouraging message at home.

One of my campers, now a prominent rabbi on the international stage, said, “the wackiness of a man disguised as a dragon jumping out of a chimney enabled us to embrace our own wackiness and not give a damn about conformity. Puff taught us to embrace our uniqueness rather than mute it or tune it out.”

Another of my favorite campers, now a top shelf Hollywood Producer, mused, “Puff made it seem like all was possible and that helped me push the envelope and not give up in my pursuit of the silly!”

If the truth be known, it was all reciprocal. Jerry Seinfeld once said, “The audience will tell you where you are funny.” The campers did that for me and showed me how best to offer myself up to my world.

The good rabbi mentioned, “What grows never grows old.” What grows starts with seeds. And these were some good seeds.